(A brief word on the illustrations I used here - the main "plates" are lightboxed from Google image results; the reference photos are linked below each image. I point this out to ensure that none of my readers say, "Wow! These are incredible renderings!" since I essentially traced them. I used this technique because I felt just using the original photos was a bit lazy, and also to isolate the bugs from the backgrounds and make their characteristics stand out).

Let me spin you a nightmare scenario: you and your friend are enjoying a beautiful summer day, when suddenly your friend gets stung. Immediately he begins to swell, showing clear signs of deadly anaphylaxis. You quickly spring into action and inject him with an EpiPen, saving his life. But one aspect of the incident continues to haunt you, sending your life into a downward spiral of shame. One question that, had you brushed up on your entomological knowledge, wouldn't make you sit bolt upright in a cold sweat:

"Was it a bee...or a wasp?!"

Thankfully, Gentle Reader, I am here to prevent this terrifying possibility by filling you in on all the wasp- and bee-related knowledge you need to get through life and its subsequent stings.

The Basics

|

| Figure 1: My criminally simplified wasp family tree |

All bees, wasps, horntails, and ants belong to the same group, the Hymenoptera ("membrane-wings" or "joined-wings", depending on who you ask). All types of these insects have some ability to fly, although in ants this is restricted to males and queens. To egregiously simplify their evolution, horntails are the more ancient members of the group, giving rise to the wasps, which then spun off bees and ants. For the purposes of this post, I'm going to leave out the ants - sorry, ants - since they're generally not the ones flying around scaring people. I'm also not going to discuss the horntails very much (with one notable exception) because they tend to stay in forests and tree canopies rather than around human habitations.

So what separates bees and wasps? At least here in the Midwest, "bee" is used for pretty much any flying, potentially stinging insect. While I'm not here to shame Just Folks for their earthy colloquialisms, I'm a scientist, dammit, and I demand precision! So I shall educate you on the very important differences between bees and wasps:

Wasps

- A massive family covering a wide variety of social, solitary, and parasitic flying insects

- Are either hunters or foragers (or both)

- Generally hairless or only slightly hairy

- Generally long-bodied with pointed abdomens and "wasp waists" between the thorax and abdomen

- Most have smooth stingers, meaning each individual can sting multiple times

- Social wasps make their nests out of paper (literal paper, made from wood fibers and spit - our modern paper manufacturing was inspired by paper wasps)

Bees

- One branch of the larger wasp family

- Can be social or solitary

- Get all their food from plant materials; some produce their own food (honey and royal jelly)

- At least partially covered in thick fuzz

- Generally stocky, with rounded abdomens and no apparent "wasp waist" (although the connection between thorax and abdomen is actually quite small)

- Most have smooth stingers, but honeybees rather famously have barbed stingers that tear out of their abdomens after stinging; each honeybee can only sting once

- Social bees make their nests out of wax, produced from a special gland in their bodies

You're probably also familiar with the term "hornet", generally used synonymously with "wasp". However, hornets are a very specific genus of wasp:

True Hornets

- All are members of genus Vespa

- All are eusocial

- More or less bullet-shaped, with heads and thoraxes of equal width and heavy, pointed abdomens - hence the term hornet, or "little horn"

- Heavily-armored, with light fuzz

- Build aerial nests

- Have a habit of preying on honeybees

- Have more painful stings than most other wasps

- Include the largest wasps in the world, the Asiatic Giant Hornet (Vespa mandarinia) infamous "murder hornet"

Eusocial vs. Solitary

Many bees and wasps are what we call "Eusocial", which means they don't just meet for Bingo, but rely on their colony for survival - in fact, they will quickly waste away and die if separated from their colony. Eusocial insects have a few, or sometimes only one, fertile female (or "queen") that produces all the infertile female workers; males are few and far between, and only exist to fertilize the queens. These insects have an astonishingly sophisticated social structure, rivaling that of some mammals. Individually, eusocial bees and wasps aren't any more aggressive than their solitary cousins; but as a swarm they can be extremely dangerous, defending their nests to the death.

Solitary bees and wasps are less well-known, but operate like most other insects, with each individual focusing on their own survival and the tending of their offspring. Solitary wasps are usually either predators or parasites, but are well-known for their tendency to paralyze their prey rather than outright killing them, giving their growing larvae the gift of, er, fresh meat to slowly eat over their development - gruesome, but very effective. Solitary wasps either nest underground or build rather astonishing mud-cells against the sides of trees, rocks, and buildings. Solitary bees nest in holes, either in wood or underground, and feed their babies pollen or a kind of regurgitated plant-food called "bee bread".

Okay! Enough of that scientific dribble-drabble. On to the various bees, wasps, and hornets you may spot in Michigan:

These adorable, extremely fuzzy (and rather large) bees are one of the premier early pollinators of the northern hemisphere. Their thick fur and ability to generate heat allow them to take advantage of early flowers, and even to colonize high mountain ranges and lands as far north as Ellesmere Island in the arctic circle. Bumblebees are mostly black with bands of yellow, white, and sometimes a ruddy orange, or a combination of the three colors; they come in various sizes, from as big as your thumb to as small as a honeybee, and even the Midwest has a surprising number of species. Bumblebees don't produce honey or even make hexagonal cones, but nest under logs and rocks (and under concrete, such as the edges of driveways) where the queen makes wax "pots" to rear her young. Once a colony is established, the bumblebees will continue to bumble their way through the summer and early fall, until the first hard frost causes the queen to hibernate. Unfortunately the remaining workers do not survive; this means that bumblebee colonies remain relatively small, rarely hitting the 1,000-member mark (as opposed to honeybees, which average 20,000-80,000 workers). Contrary to popular belief, bumblebees do sting, but are pretty reluctant to do so unless their nests are disturbed or an individual is harmed.

Western Honeybee (Apis mellifera)This is your standard Eurasian honeybee, cultivated by humans for thousands of years but only introduced to North America in the 17th century to help pollinate introduced crops. Honeybees are now established across most of the earth's nonarctic landmasses. Honeybees obviously nest in artificial hive boxes, but in the wild they tend to nest in hollow trees; from early- to mid-spring, they swarm in spectacular hurricanes of bees as they establish a new nest (if you've never experienced a bee swarm, I can personally attest that it is a spectacular event). Honeybees construct their nests out of layered, undulating sheets of beeswax with hexagonal cells, allowing for advanced airflow to prevent overheating and fungal growth; some of these cells are "brood cells" for larvae, while most are used for honey storage, which will sustain the colony as they overwinter. Just like most of our domesticated animals, honeybees have been bred for high production and tolerance to humans; but honeybees are still responsible for more deaths than any other animal, including cows (which kill an enormous number of people every year).

Speaking of death, what about "Killer Bees"? These are actually a hybrid of European honeybees with an African subspecies. The problem was that Western honeybees were having trouble in South America, where the high temperatures were depressing honey production and causing bees to not defend their nests effectively against predators. African honeybees were noted for their heat-tolerance and disease-resistance, as well as for their extreme aggressiveness in defending their nests. By combining the high honey production of European bees with the toughness and aggression of African bees, scientists hoped to create a tropical "superbee". As you might have gathered, the results of this Frankensteinian experiment escaped, and quickly established colonies across South America and began their steady march north. These "Africanized" honeybees are now to be found in the southwest, as far north as central Nevada and as far east as east Texas. Africanized honeybees earn their reputation not through more venomous stings or larger size, but because of their readiness to attack anything approaching their nest; the sheer number of workers involved in each attack (over a hundred times more than European honeybees); and the distance they will chase a fleeing victim (over a quarter-mile). Africanized honeybees have already killed over a thousand people, and constitute a huge public-health problem in parts of the United States.

Northern Paper Wasp (Polistes fuscatus)This is one of the most common paper wasps in the Midwest, and are notable for being mostly black-and-red, most significantly in the reddish "eye spots" on its abdomen (other color morphs are present across North America). As their name suggests, paper wasps build their nests out of a tough paper material made of wood pulp and saliva, extruded into hexagonal cells to make an open-faced "umbrella" nest, attached to a surface (often the corner of a building) by a narrow, tough stalk. The wasps forage nectar, pollen, and small caterpillars, which they bring back to regurgitate for their young. Colonies consist of an initial fertile "foundress" who builds the nest, then broods a first generation of infertile female workers, then a second generation of fertile female foundresses; when the new foundresses mature, they battle amongst themselves for dominance. Amazingly, once the social hierarchy is established, the foundresses all work cooperatively to raise young and assist the colony. More-dominant foundresses will literally stand taller than their subordinates, and individual wasps - even the workers - can recognize each other by their unique facial markings! This strangely "vertebrate" behavior of cooperation and individuation makes each colony less like a hive, and more like a motorcycle gang. Northern paper wasps are generally harmless to humans, and will even allow a close approach (anyone who's opened their shed door to find ten paper wasps staring at them can attest to this), but their tendency to nest in doorways often brings them in conflict with humans. Small colony size and a relatively uncoordinated defense (as opposed to honeybees) means northern paper wasps aren't all that dangerous except in case of beesting allergy (but tell that to somebody being mobbed by them).

I wanted to end this segment with an interesting footnote: way back in the day my dad cut down a hickory in our backyard; while poking around through the refuse I was startled by what I thought were black wasps, hovering around the cut limbs. But when I looked closer, I realized these were no wasps - they were a kind of longhorn beetle with red head and thorax, and a black-and-yellow abdomen. While their color patterns didn't stand up to more than superficial scrutiny, their loopy flight pattern, their landed movements (head twitching, jerky legs, flicking their wing covers), and even their habit of congregation, looked exactly like those of the Northern Paper Wasp. This beetle is called the Red-Headed Locust Borer (Neolyctus acuminatus), eater of dead and diseased hardwoods and scourge of lumberyards. This is an example of Batesian mimicry, in which a harmless animal copies the colors and/or habits of a dangerous animal in order to warn away predators. I'm still fascinated by this beetle - how did it develop the instinct to act like a wasp? - and hope I encounter them again in the future.

Eastern Yellowjacket (Vespula maculifrons)These are the dreaded "Ground Bees" that ruin many a picnic and tend to nest in backyards and in the foundations of buildings. They are small, mostly yellow with black markings, and somewhat hairy; they look like little hornets, and often behave the same way. They are significant predators of caterpillars - I've personally seen two yellowjackets peel and eat a green caterpillar like a banana - as well as visitors to animal carcasses; but they are best-known for their obsession with sweets, swarming picnic tables where sugary drinks or candy are present. They are fairly tenacious in their pursuit of food, often hovering in front of childrens' sticky faces and increasing the chances of a sting; their nest-holes are often very inconspicuous, making it easy to trod on them by accident and invite a horde of angry defenders. Those who have attempted to remove their nests have experienced these wasps' resilience against water, fire, and many kinds of poisons.

In my personal experience, I've had up to three nests operating in my cool, well-shaded backyard at once. I found the nests by almost stepping on them; in all cases, I never received a single sting, and have been able to closely observe the insects without incident (Note: don't try this at home!) I have a couple of theories as to why this is: 1) the cooler conditions made the insects less likely to attack: around the same time, my nieces were traveling through a sunny field near their home, and were almost immediately attacked by the yellowjackets nesting there. At the same time, my colonies weren't lethargic at all, zipping around the yard and going in and out of their holes at regular intervals. 2) It may be because I remain calm and don't exhibit panicked behavior in the face of wasps and bees; this calmness allows me to approach the colonies and observe them relatively closely. Ultimately I decided to leave the yellowjacket colonies be, since the backyard isn't typically used by visitors and the wasps weren't causing much of a nuisance. I was surprised, however, to find some of the colonies disturbed one morning, with large holes dug around the colony entrances; the only clue was the smell of skunk lingering in the air. African honey badgers were known to raid bee nests for their nutritious larvae; do skunks perform the same function here in North America? At any rate it was good to know that something was keeping down the numbers of these aggressive, numerous wasps.

German (European) Wasp (Vespula germanica)This European cousin of the yellowjacket is a very troublesome invasive species, known to build its aerial football-shaped nests near humans and aggressively outcompete native species. They've become established worldwide, even in New Zealand, where they are considered a threat to many native vertebrate and invertebrate species. Physically they're almost identical to eastern yellowjackets, just larger, longer, and having more black on their markings and abdomen (and of course not living underground). Even worse, there are several other native yellowjackets that look almost identical; thankfully there are plenty of identification charts online, so you can follow yellow wasps through your backyard and beg them to sit still so you can decide whether or not they are invasive.

Bald-faced Hornet (Dolichovespula maculata)These wasps are rather unique for their white-and-black markings (hence the term "bald", which used to mean "white" - same for the bald eagle). Though called hornets, they are in fact a kind of aerial yellowjacket, as there are technically no native true hornets in Michigan (yeah yeah, I know...) These wasps are medium-sized, chunky, and hairless; they build gray paper "football nests" high in trees, wrapping the base around thin twigs. Since they stay high up in the canopy, humans are unlikely to encounter these wasps...unless the twig snaps. Then the wasps will attack passersby en masse, using their unique defense of squirting venom into the eyes like a spitting cobra! There is, however, a specific case where you can safely encounter many bald-faced hornets at once: fallen fruit, particularly pears, attract the wasps in droves, we they literally get drunk on the fermenting sugars and stumble around, flying into things and getting into brawls with one another. Whether or not the wasps enjoy this experience isn't known, but they do it a lot, so they must be getting something out of it.

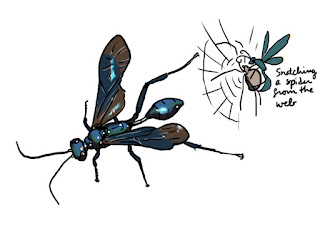

Black-and-Yellow Mud Dauber Wasp (Sceliphron caementarium) This is the ultimate wasp-waisted wasp, with its abdomen mounted on a long stalk. This thin wasp is very distinctive as it visits flowers and hovers around building foundations, looking for suitable nest locations. As their name suggests, these wasps build cells for their offspring with mud and spit, often in an existing hole or in the corner of a building where the nest will remain cool. Mud daubers prey on spiders; their MO is to blunder into a web, causing its occupant to fall to the ground and run off; the BYMD then tracks the fleeing arachnid. If they find it (or run across a different spider), they paralyzing their prey with a sting; they then bring them back to their nest, lay an egg on them, and then seal the spider up inside a cell with more mud. If nice fat spiders cannot be found, the wasp will cram as many small spiders into its cell as possible. The larvae will then hatch and begin to consume the spider, starting with the extremities and saving the heart for last, ensuring a constant supply of fresh spider flesh (there's a sentence you don't type every day...) Black-and-yellow mud daubers are unique for their males' defense of the nest, watching over it to ensure that other wasps don't try to steal it - like, for instance...

Blue Mud Wasp (Chalybion californicum) This is a beautiful cousin of the mud dauber wasp, sometimes known as the "Black Widow-killer" for its predation of the dangerous spider. This wasp is metallic blue with black wings, and moves with a twitchy nervousness, tapping its antennae and flicking its wings - it probably needs this twitchiness to react to its lightning-fast, venomous prey. Blue mud wasps are much cleverer than their black-and-yellow cousins; they land carefully on the webs of their quarry, then twitch the threads to imitate struggling prey. When the spider rushes out to attack, the wasp deftly pounces and immobilizes the spider with a sting. Blue mud wasps are known to appropriate the nests of mud daubers, using water to soften the nest, throw out the spiders (along with the original wasps' eggs), and plant its own spider-and-egg combo before sealing up the lot with more mud.

While mud wasps do sting, they and their solitary cousins are more likely to avoid humans, as there is nothing of ours they want (except the cool side of a building). Leave these pollinators alone, and they will deal quite efficiently with your ever-present crop of spiders.

Leafcutter Bee (Megachilidae ssp.) These honeybee-sized, dark-brown to -black solitary bees emerge en masse in early spring, and begin looking for a nice hole to build their nests; they can often be found hovering around porches where they can find a convenient nail-hole. As their name suggests, they use their jaws to cut leaves to line their nests. They are willing to tolerate each others' company, often nesting together where many holes are available, but will fight each other for mating rights and territory. They rear their young in the hole, feeding it pollen.

I recall seeing these bees congregating along a country roadside on a warm day in April; they appeared to be patrolling and defending small patches of soil. The soil in question was next to a cornfield, still moist from rains the night before, and the roadside was dotted with spilled manure from farm trucks; were these bees seeking out minerals and nutrients, or were they defending nest-building material? I do recall seeing some bees fighting one another, and even a severely-wounded bee with half of its head missing; whatever these bees were defending, they were willing to kill each other for it. Based on what I know about insect behavior, I believe that these were males, staking out and defending "mud patch" to attract a female, who would then use the mud to help build her nest. But where would the females build their nests? I wonder if old, hollow cornstalks, left over from last years' harvest, might make a tempting brood-site (at least until the plow comes along...)

Carpenter Bee (Xylocopa virginica) These are large, heavy-bodied solitary bees often mistaken for bumblebees; they can be distinguished by their brown and black coloration, bald patch on their thorax, nearly bald head and abdomen, and heavy jaws, which they use to bore holes in wood. They are often found around porches, patrolling their territory like tiny helicopters, hovering nearly motionless until another bee crosses their path. Though they can sting, carpenter bees fight primarily with their huge jaws, with which they can easily kill rival bees. Once their young have hatched, they feed them with a regurgitated pollen-and-nectar mixture called "bee bread". Carpenter bees can sting, but they are pretty unaggressive; their worst offense is their hole-boring habits - some holes are up to six inches long, and each bee can brood several times a year. Long-term infestation can even cause structural collapse!

Giant Ichneumon (Megarhyssa macrurus) This may have been the inspiration for Alien. Ichneumon* wasps are notorious for attacking wood-boring grubs, drilling down through the wood into their chambers, paralyzing them with a sting, and injecting an egg into their bodies. The larva then eats the grub alive before bursting out of its body, spinning a cocoon, and developing into an adult wasp. The Giant Ichneumon is probably the most spectacular example of this parasite. With a 2-inch body and 3-inch ovipositor trailing behind it, this intimidating and beautiful red, black and white wasp buzzes through North American hardwood forests like a sky-crane, seeking out the diseased old oaks and elms where its prey resides. The ichneumon detects a larva by smell or vibration, sometimes two inches or more under the bark, then arches its abdomen and guides its ovipositor into position. Its ovipositor is a 3-part engineering marvel with two barbed, metal-tipped cutting mechanisms surrounding a stabilizing core; this allows the wasp to thread between the tough wood fibers instead of trying to force its way through. Though the ovipositor looks like it could fuck you up, it's simply too long and whiplike to use as a defensive stinger, so humans are absolutely safe from the Giant Ichneumon.

My encounter with this amazing creature occurred in the Hoosier National Forest in southern Indiana. On a steamy late-June afternoon, I stepped off the trail to investigate a huge fallen tree humming with beetles and other creepy-crawlies. Suddenly a huge insect droned past my head, causing me to duck; the sunlight filtering down through the canopy caught its gossamer wings and trailing filaments as it hovered over the massive log, making several passes before landing on its stiltlike legs. It made no move to escape as I carefully approached, watching as she drummed the bark with her antennae, and then began the eerily graceful process of curling her abdomen and flicking her ovipositor sections into position, ready to attack her doomed larval prey.

While most ichneumons attack beetle grubs or caterpillars, Giant Ichneumons target another hymenopteran species: the larvae of the equally large and strange...

Pigeon Horntail (Tremex columba) Horntails (or wood-wasps) are some of the more neglected Hymenopterans; they generally avoid humans, and though often wasp-colored, don't really look or act like wasps at all. Being a more "primitive" form of hymenopteran, they don't exhibit the wasp-waist, instead having a relatively tubelike body; none of these insects sting, instead using their ovipositors exclusively for drilling through wood and depositing their eggs. The Pigeon Horntail is about 2" long - a big bug - and primarily black, with red-brown and dull-yellow accents; the term "horntail" derives not from the females' stiff ovipositor, but from a pointed projection on the end of their abdomen that is present in both sexes. Pigeon horntails seek out diseased or dying hardwoods such as elm or oak, where they choose a location near the base of the tree and begin drilling, using a similar (but even more efficient) mechanism to the ichneumon wasp. Once a suitable depth has been attained, the horntail deposits a packet of white-rot fungus along with a single egg; the fungus spreads quickly through the wood, softening it and concentrating sugars before the egg hatches and allows the newborn maggot to feed. It is when the larva is at its largest - usually after about 2 years - that it is most vulnerable to Giant Ichneumon attacks, as it is as large as its parent, and can't hide its chewing and movement from the extremely sensitive ichneumon. This complex chain - of hardwood trees, wood-boring prey, symbiotic fungus, and species-specific predator - is one of the natural wonders of the northern forest; if any one of these elements is removed, neither of these magnificent insects will survive.

You may have been wondering, through this whole segment: why is it called a pigeon horntail? The answer is: nobody knows. Our old buddy Carl Linnaeus gave the insect its specific name, columba, which literally means "pigeon". Was it because it flies like a pigeon? Mostly they just buzz around, like any other wasp. Was it the milling, circling movements they make as they look for a suitable drilling-site? I'm no scholar on Linnaeus, but it's safe to assume that an 18th-century naturalist wasn't doing his own fieldwork - he just received preserved bugs on a shipment from the Americas. Was it some folksy Swedish idiom, i.e., "Gode Gud! It's as big as en damn pigeon!!" Or maybe old Carl was just on his fifth coffee-and-laudanum, and was using some, er, "creative" naming conventions? My research has turned up nothing on the matter except more head-scratching; maybe someday I'll figure out this conundrum.**

Velvet Ant ("Cow-Killer") (Dasymutilla ssp., et al)They look like colorful, furry ants, but don't be fooled: these are wasps, and they pack a mighty sting. "Velvet Ant" refers to the flightless female of the species; the rarely-seen males look like rather ordinary (albeit fuzzy) wasps, visiting flowers and generally not making a nuisance. The females prey on the young of ground-nesting bees and wasps, laying their eggs inside the brood chambers where they can devour their helpless prey in peace (sensing a pattern here?) Velvet ants are known for their extremely long and painful stingers, and one species in particular,

Dasymutilla klugii, rates about a 3.0 on the humorous and strangely poetic

Schmidt Pain Index - about the 4th most painful sting, behind Bullet Ants, Tarantula-Hawks, and Warrior Wasps. Strangely, velvet ants are also known for their extremely strong exoskeletons, which are 11 times more crush-resistant than a honeybee. Why this is, science can't yet explain; I'd argue that it might save the little parasitoids from the jaws of defending bee or wasp parents who might take exception to velvet ants' brooding habits.

I've had two encounters with velvet ants: the second was with a quite small, unassuming species around the Gregory, Michigan area: mostly hairless, dull red, and having black-and-white stripes on the end of its abdomen.*** I found it in association with a migrating swarm of Thatcher Ants (Formica obscuripes); I don't know if it was simply traveling alongside them, or if it preyed on the ants themselves, or if its appearance was simply coincidental. The second encounter was with the Cow-Killer itself, Dasymutilla occidentalis, in the Hoosier National Forest; this insect was larger, with a bright red-orange and black pelt. Capturing the insect (carefully, for I had heard of its reputation), I pinned it gently with a stick, at which point it began making a squeaking chirp called "stridulation" and extruding its unbelievably long, wicked-looking stinger; it was as long as the bug itself! I released the cow-killer off the trail in an area where, hopefully, nobody would step on it and experience that dreadful stinger for themselves. Obviously this insect can't actually kill a cow, but I'm sure the unfortunate bovine would have a very bad time.

Eastern Cicada-Killer (Sphecius speciosus) Our final entry into this litany of flying wonders is the largest native wasp in North America. Coming in at 2.5 inches (the female is a third larger than the male), the Cicada-Killer is a huge mud-wasp which, as its name implies, predates cicadas: to repeat the oft-heard horror story, it paralyzes its prey with a sting, then hauls it back to its burrow, lays an egg on it, and the larva will consume the still-living insect, leaving the heart for last. Eastern Cicada-Killers are mostly black with red or yellow accents, and white stripes on their large abdomens; their first pair of legs are held close to the chest like a mantis, all the better to grasp their prey. They nest in sandy or loose-soil environments, and will tolerate other cicada-killers and even share a burrow between several females. Males will defend burrows and fight vigorously for territorial rights; although the wasps are large and intimidating as they grapple, they ignore humans, and will allow a quite close approach. The females are notable for being able to lift huge weights, since their prey is almost twice as heavy; even so, some have to haul their quarry to higher branches in order to make it back to their burrow.

My personal encounter with Cicada-Killers was at a Scout camp near Gregory, MI, where I had worked for several years; I hadn't seen cicada-killers in this location before, so the running theory was that they had experienced a population boom to coincide with a flush of cicadas.**** I was fascinated by these insects, spending whatever free time I had observing their antics. At some point I noticed three or four males ganging up on one giant female, brandishing their stingers in their frenzied attempts to mate with her and kill the other males, sometimes attempting to sting the female, though her armor was too tough to penetrate. The sight of those crawling, pulsating bodies was both horrifying and hypnotic as they twisted and crawled over one another, their desperation palpable. I'm not going to call it erotic, because that would be weird, and I definitely did not experience confusing bug-sex feelings.

And the cold shower I took later was definitely unrelated. Because that would be really weird.

The Takeaway

Obviously there are many, many, many more fascinating bees and wasps to explore; I've just given you a tiny taste of the diversity you can find in the Midwest, from the city to your local woodlot. The main takeaway here is that, instead of just running in terror from our winged friends, we should take a deep breath and allow ourselves to look a little more closely. Obviously bees and wasps can be dangerous, especially in their nests, and I'm obviously not encouraging you to stick your head in a hornet's nest...don't do that. Especially if you're allergic. But if a bee or a wasp lands on a flower and seems intent on gathering nectar and pollen, just get close enough that you can observe their beautiful colors and impressive body plans. And if a bee suddenly hovers in front of you, stand still and wait; it's merely curious about your shape and smell, observing you like a scientist - flailing will only frighten it and increase the chance of a sting. And even if you really don't want to get anywhere near them, at least plant native flowers and plants for these amazing pollinators, or look online and find plans for "bee homes" that will attract pollinators to your garden (and hopefully away from your house and porch). And please, if at all possible, don't use chemicals - pesticides and herbicides build up in flowers and prey that bees and wasps need to survive, severely harming our insect friends. Yards don't have to just be for grass; keeping a natural lawn and garden, with an emphasis on native species, will help bring balance to your local environment.

Rick Out!

* A quick word on "ichneumon": this was a Medieval name for the Egyptian Mongoose. Legend had it that the mongoose could kill crocodiles by waiting for them to open their mouths, then jumping down their throats and disemboweling them from the inside out. I'd argue that this is slightly less horrifying than paralyzing the crocodile and depositing baby mongooses inside its body so they can slowly consume it over a period of years, but y'know...

**I jest of course; I have no reason to slam our old buddy Carl. Unless he turns out to be a huge racist or a slaveowner or something, which wasn't unusual for that time. I'll have to read up on him.

***This specimen may not have been part of the Dasymutilla genus - the Mutillidae family is vast, with over 7,000 members; it may have been Pseudomethoca frigida, for instance, which looks exactly like a miniature Dasymutilla foxii. Entemologists describe "rings" (like "criminal rings") of velvet ants in certain regions which share the exact same coloration, in a process called Muellerian mimicry - they're all painful to some degree, so sharing coloration ensures that predators learn to avoid the whole group.

****Cicadas are famous for staying underground for a decade or more before emerging. The black-and-orange periodical cicada (Magicicada septendecem) stays underground for 13 to 17 years, before emerging en masse as a plague of "locusts". However, cicada-killers seem more interested in the Annual Cicada (Neotibicen ssp.), which staggers its emergence so that the species is present every year. Every few years the Annual Cicada emergence synchronizes to form a population boom, and the Cicada-Killers seem to time their own breeding to coincide with this.

Comments