So as you may know, I am partly obsessed with dinosaurs. Scratch that - there's a small lobe of my brain devoted to dinosaurs. I love em, God help me. I even have a super-double-plus-top-secret dinosaur comic maybe in the works...but you didn't hear it from me.

Anywho...

Part of my problem is in the reconstruction of said prehistoric beasties, namely those icons of American dino-obsession, Deinonychus (Velociraptor to you Jurassic Park aficionados...it's not just a Hollywood bastardization, there's a complicated story behind it which I covered in this old post). Now, we all know what Deinonychus looked like: wolf-size, sleek, toothsome head balanced by a long tail, grasping front claws and of course the eponymous "terrible claw" on its hind foot. The shape is burned into our collective unconscious; you could construct the most fantastic amalgam of different bits and pieces, but as long as you include the sickle-claw, you're golden.

The devil, of course, is in the details.

(Disclaimer: I'm not a paleontologist by any means, merely an enthusiast. Everything I say and reconstruct here should be taken with a grain of salt).

Item one: what does Deinonychus' head actually look like?

Here's the classic skull-shape. I call it the "Allosaur" version, since it resembles the much larger theropod:

(from Wikipedia)

Now here's Gregory S. Paul's reconstruction (couldn't find just the skull) from his 1988 book, Predatory Dinosaurs of the World:

(©1988 Gregory S. Paul)

As you can see, the skull shape is quite long and sort of rectangular. I'll refer to it as the "Velociraptor" version, since it looks more like Deinonychus' smaller cousin.

You see the issue? The Allosaur-type skull is, as far as I know, the original reconstruction by John Ostrom in the late 1960's. So whence the reconstruction Mr. Paul based his illustrations on? Obviously I defer to Mr. Paul's experience and scholarship in the matter; I'm just trying to retrace the steps leading up to the "new look".

Wikipedia helps shed some light on the issue. From the Deinonychus page:

Studies of the skull have progressed a great deal over the decades. Ostrom reconstructed the partial, imperfectly preserved skulls that he had as triangular, broad, and fairly similar to Allosaurus. Additional Deinonychus skull material and closely related species found with good three-dimensional preservation[6] show that the palate was more vaulted than Ostrom thought, making the snout far narrower, while the jugals flared broadly, giving greater stereoscopic vision. The skull of Deinonychus was different from that of Velociraptor, however, in that it had a more robust skull roof, like that of Dromaeosaurus, and did not have the depressed nasals of Velociraptor.[7] Both the skull and the lower jaw had fenestrae (skull openings) which reduced the weight of the skull. In Deinonychus, the antorbital fenestra, a skull opening between the eye and nostril, was particularly large.[6]

That clears up part of the mystery: according to more receont fossils, Deinonychus had a skull-shape more closely related to that of its Asian cousin Velociraptor. At the same time, this leads to another question: what exactly did the skull look like?

I ask this because I have seen many different reconstructions, even within the pages of Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. I have a sneaking suspicion we really don't know exactly what a Deinonychus skull looked like. Most of the fossilized remains of this animal are quite scattered and fragmentary, as befits a lightly-built predator with a violent lifestyle; most of the skeletal reconstructions in museums are filled in with educated guesses. Their skulls are especially elusive because they are less robust than the other bones.

For my purposes - since the shape of Deinonychus' skull is less than definitive - I'm going to split the difference between Ostrom's and Paul's versions. The result will be a dog-faced look, as befitting Deinonychus' wolflike demeanor. Here's the best example I've found of this:

(sculpt by Jason Brougham)

This skeletal reconstruction, by the way, is probably the most convincing I've ever seen. Here's a better view:

(sculpt by Jason Brougham)

You get a lot of bad paleo-art out there; it's nice to see someone finally knuckling down and doing the heavy-lifting of reconstruction work - that is, taking the time to look at the measurements and get the proportions down just right. Kudos to Jason Brougham for his excellent model!

One thing I especially like about this model (if I can pick one) is that it demonstrates extremely well the defining features of the dinosaur: its hands and feet.

Let's talk about the feet first. There's a lot of debate as to the actual speed of this animal. Jurassic Park gave its Raptors "cheetah speed", in the words of the character Robert Muldoon. This is to imply a running speed of 50-60 mph. The problem comes in the upper foot bones of the dinosaur, which are actually quite short; a running animal needs relatively long, simplified "cannon" bones, which are the pistons driving its momentum. See, for instance, the tarsals of the ostrich, which are extremely long and fused:

(from Pinterest)

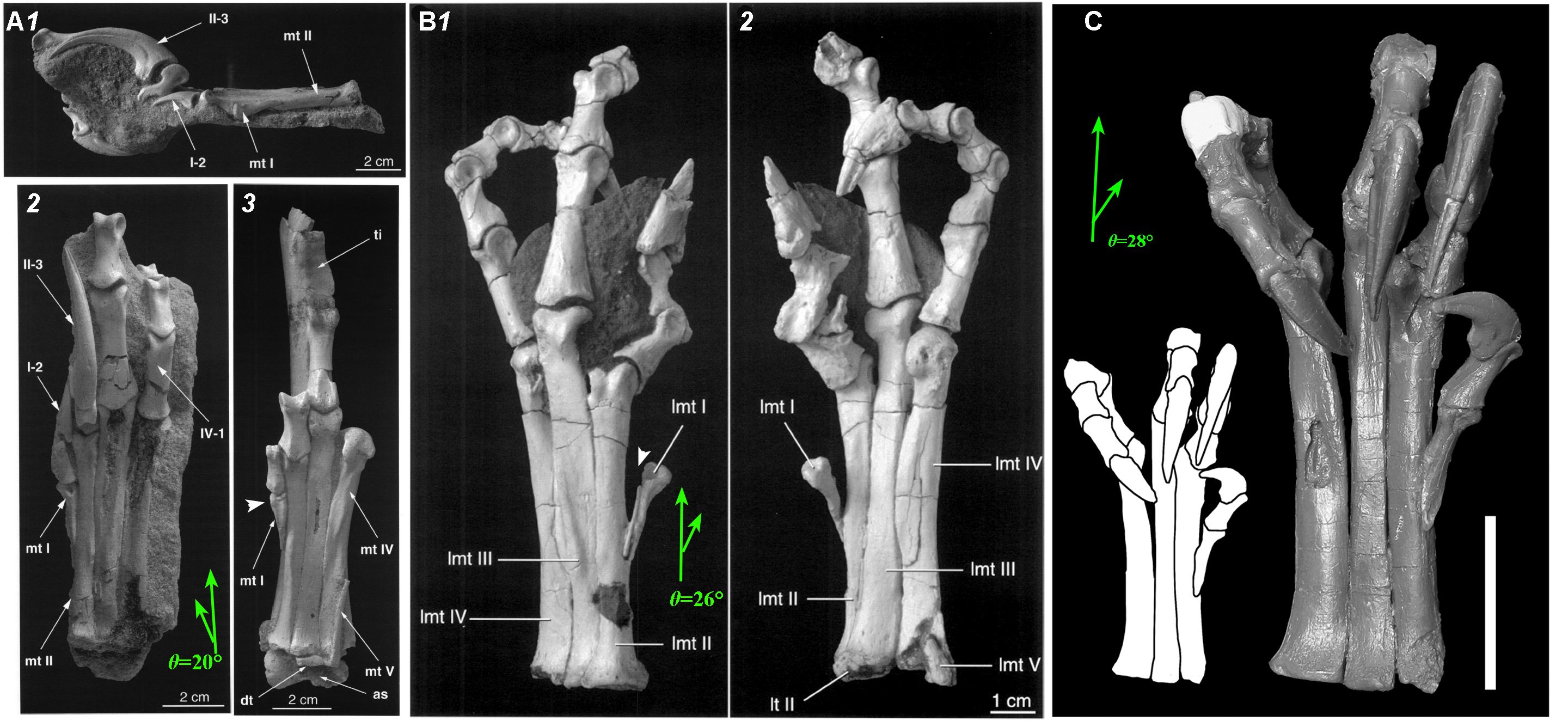

Here's a study of the pes (tarsals and metatarsals) of Velociraptor and Deinonychus:

(Reconstruction by Denver Fowler, Elizabeth Freedman, John Scannella and Robert Kambic)

As you can see, the "running bones" of Deinonychus were really, really short. We can therefore surmise that this animal was, at least, not a very powerful runner.

That doesn't mean it wasn't quick. Predators the world over have demonstrated that quickness and surprise often win out over amazing speeds. Only cheetahs, in fact, really go for the flat-out chasing-down of prey over distance, and they're not really efficient predators.

Taking a different tack, here's a skeleton of a speedy creature which doesn't run at all:

That's a red kangaroo, which locomotes entirely by hopping. Note the relative shortness of the foot bones. Now, I'm not speculating that Deinonychus chased down its prey like a hellish wallaby (although that would be interesting...); rather, the similarity in the proportion of leg bones implies (or at least doesn't rule out) an impressive jumping ability. Once Deinonychus got within leaping distance of its prey, it would be able to quickly attach itself with its claws and begin the gruesome work of kicking its prey to death. Even without immediately killing its prey, the pack could then track the wounded animal, biding its time until blood loss and infection did all the heavy lifting, and Deinonychus could deliver the coup d'etat.

A quick note about the "terrible claw" itself: here's a pretty good BBC doc about Velociraptor mongoliensis in which they tested models of the back leg of these creatures. Interestingly, the claw wasn't built to disembowel: the underside of the scythe was round and dull, with no serrations. Only the point was sharp. The claw was therefore used as a stabbing weapon, puncturing arteries and trachea in the neck area.

Now for the hands.

There's currently a craze for showing Deinonychus as a sort of heavily-feathered, land-roving hawk - much of this owing to the work of Fowler et al. (see above). Here's another image from their work:

Now, I'll admit to a certain bias; I'm definitely of the Jurassic Park generation, which would love to view Deinonychus as an intelligent, wolf-like packhunter, with dexterous killing hands. I also applaud the authors of this paper for having the courage to go against decades of accepted orthodoxy on the subject, and offering an alternative view of these amazing creatures.

At the same time, I have some deep problems with their reconstruction of Deinonychus arm function. The main thrust of the paper is that Deinonychus used "stability flapping" to maintain its balance atop a prey animal that was probably very much alive, then "mantled" the prey, as hawks do, both to prevent prey escape and to discourage other dinosaurs from poaching its catch. This predation behavior, according to their hypothesis, eventually leads to flapping in birds, and thus flight. The paper goes on to say that, since the wrist bones of Deinonychus were relatively stiff, this would proclude the kind of "snatching" behavior one would assume from such long, powerful hands.

This, to me, seems rather nonsensical. In dinobirds such as Archaeopteryx, which had nearly birdlike wings, the fingers are thin and trailing, with rather small claws. In Deinonychus, the fingers are very robust, with enormous claws. I fail to see why even a transitional animal would sport such massive, powerful front claws if they were only used for flapping and mantling.

This isn't just curmudgeonly fussing on my part, either. Let's look at some fossils. I present to you the famous "fighting dinosaurs" of Mongolia:

I believe this to be the original, and not a reconstruction - feel free to let me know if I'm wrong. On the left you see a Protoceratops; on the right, a Velociraptor. The 'raptor's right arm is caught in the Proto's beak, while the predator is slashing at the herbivore's neck with its sickle-claws (see above). Note the position of the left arm: it is clearly raking at the Proto's cheek bone, with the wrist flexed, and all the claws facing in the same direction - more like a hand than a wing.

Here's the same fossil, with more rock around it:

I include this version to show that the first image is as close to the original, intact fossils as possible, to rule out the possibility of scientific license. You can clearly see the raptor's left arm in the center of the fossil group, performing a very clear raking action. This is not to say that the Velociraptor did not perform a flapping action at some point; rather, that the hands of the creature were at least involved in some form of grasping, with the possibility of wrist torsion. In other words, the hands of Dromeosaurids (Deinonychus, Velociraptor, et al.) were involved in holding prey.

Here's a dinosaur-to-bird progression from David Peters over at Pterosaur Heresies:

This view, especially of Velociraptor, shows the joints especially well. (As to whether or not Dromaeosaurids could torque their wrists is a whole other issue; most recent reconstructions show them locked in place. I'd like to see the original fossils).

This leads me to a second issue, and one which continues to bother me about the recent crop of paleo-art: the assumed mass of Deinonychus' feathers.

"Feathered Dinosaurs and the Origin of Flight" traveling-exhibit model

The above model was originally just scaly, with the feathers added later. I'm actually okay with the majority of this reconstruction...except for the ludicrous, gauzy plumes attached to the hands. Did somebody go cheap at the feather emporium? Did they run out of primaries? Just looking at those arm-curtains gives me the itch for a big ole pair of scissors. Yuch.

Anyway...my problem with fully-winged arms, is that all those large feathers are a liability for an active predator. Assuming Deinonychus used its hands for grasping prey (which I do), long quills projecting past the fingers would get in the way, not to mention create drag in the attack. My problem is not with the idea of large feathers on the forearms, but of feathers that could interfere with gripping work.

I've developed a sort of "hybrid" interpretation: Deinonychus' arms utilized the downstroke of a flapping motion (see the large breastbone) alongside a forward snap of the hand. Here's a picture of the movement:

Whether or not the fingers had a full range of flexion (i.e., curl up into a fist) is irrelevant; all they needed to do was rotate the claws inward enough to grip into the prey.

As far as pelage goes: we do know that many of Deinonychus' relatives were covered in feathers; in fact, there is strong evidence that Velociraptor had quill-points on its forearm bones. It's no stretch of logic to conclude that Deinonychus itself was covered in feathers.

I favor this reconstruction, cropped from the "Feathered Dinosaurs" exhibit:

Anywho...

Part of my problem is in the reconstruction of said prehistoric beasties, namely those icons of American dino-obsession, Deinonychus (Velociraptor to you Jurassic Park aficionados...it's not just a Hollywood bastardization, there's a complicated story behind it which I covered in this old post). Now, we all know what Deinonychus looked like: wolf-size, sleek, toothsome head balanced by a long tail, grasping front claws and of course the eponymous "terrible claw" on its hind foot. The shape is burned into our collective unconscious; you could construct the most fantastic amalgam of different bits and pieces, but as long as you include the sickle-claw, you're golden.

The devil, of course, is in the details.

(Disclaimer: I'm not a paleontologist by any means, merely an enthusiast. Everything I say and reconstruct here should be taken with a grain of salt).

Item one: what does Deinonychus' head actually look like?

Here's the classic skull-shape. I call it the "Allosaur" version, since it resembles the much larger theropod:

(from Wikipedia)

Now here's Gregory S. Paul's reconstruction (couldn't find just the skull) from his 1988 book, Predatory Dinosaurs of the World:

(©1988 Gregory S. Paul)

As you can see, the skull shape is quite long and sort of rectangular. I'll refer to it as the "Velociraptor" version, since it looks more like Deinonychus' smaller cousin.

You see the issue? The Allosaur-type skull is, as far as I know, the original reconstruction by John Ostrom in the late 1960's. So whence the reconstruction Mr. Paul based his illustrations on? Obviously I defer to Mr. Paul's experience and scholarship in the matter; I'm just trying to retrace the steps leading up to the "new look".

Wikipedia helps shed some light on the issue. From the Deinonychus page:

Studies of the skull have progressed a great deal over the decades. Ostrom reconstructed the partial, imperfectly preserved skulls that he had as triangular, broad, and fairly similar to Allosaurus. Additional Deinonychus skull material and closely related species found with good three-dimensional preservation[6] show that the palate was more vaulted than Ostrom thought, making the snout far narrower, while the jugals flared broadly, giving greater stereoscopic vision. The skull of Deinonychus was different from that of Velociraptor, however, in that it had a more robust skull roof, like that of Dromaeosaurus, and did not have the depressed nasals of Velociraptor.[7] Both the skull and the lower jaw had fenestrae (skull openings) which reduced the weight of the skull. In Deinonychus, the antorbital fenestra, a skull opening between the eye and nostril, was particularly large.[6]

That clears up part of the mystery: according to more receont fossils, Deinonychus had a skull-shape more closely related to that of its Asian cousin Velociraptor. At the same time, this leads to another question: what exactly did the skull look like?

I ask this because I have seen many different reconstructions, even within the pages of Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. I have a sneaking suspicion we really don't know exactly what a Deinonychus skull looked like. Most of the fossilized remains of this animal are quite scattered and fragmentary, as befits a lightly-built predator with a violent lifestyle; most of the skeletal reconstructions in museums are filled in with educated guesses. Their skulls are especially elusive because they are less robust than the other bones.

For my purposes - since the shape of Deinonychus' skull is less than definitive - I'm going to split the difference between Ostrom's and Paul's versions. The result will be a dog-faced look, as befitting Deinonychus' wolflike demeanor. Here's the best example I've found of this:

(sculpt by Jason Brougham)

This skeletal reconstruction, by the way, is probably the most convincing I've ever seen. Here's a better view:

(sculpt by Jason Brougham)

You get a lot of bad paleo-art out there; it's nice to see someone finally knuckling down and doing the heavy-lifting of reconstruction work - that is, taking the time to look at the measurements and get the proportions down just right. Kudos to Jason Brougham for his excellent model!

One thing I especially like about this model (if I can pick one) is that it demonstrates extremely well the defining features of the dinosaur: its hands and feet.

Let's talk about the feet first. There's a lot of debate as to the actual speed of this animal. Jurassic Park gave its Raptors "cheetah speed", in the words of the character Robert Muldoon. This is to imply a running speed of 50-60 mph. The problem comes in the upper foot bones of the dinosaur, which are actually quite short; a running animal needs relatively long, simplified "cannon" bones, which are the pistons driving its momentum. See, for instance, the tarsals of the ostrich, which are extremely long and fused:

(from Pinterest)

Here's a study of the pes (tarsals and metatarsals) of Velociraptor and Deinonychus:

(Reconstruction by Denver Fowler, Elizabeth Freedman, John Scannella and Robert Kambic)

As you can see, the "running bones" of Deinonychus were really, really short. We can therefore surmise that this animal was, at least, not a very powerful runner.

That doesn't mean it wasn't quick. Predators the world over have demonstrated that quickness and surprise often win out over amazing speeds. Only cheetahs, in fact, really go for the flat-out chasing-down of prey over distance, and they're not really efficient predators.

Taking a different tack, here's a skeleton of a speedy creature which doesn't run at all:

That's a red kangaroo, which locomotes entirely by hopping. Note the relative shortness of the foot bones. Now, I'm not speculating that Deinonychus chased down its prey like a hellish wallaby (although that would be interesting...); rather, the similarity in the proportion of leg bones implies (or at least doesn't rule out) an impressive jumping ability. Once Deinonychus got within leaping distance of its prey, it would be able to quickly attach itself with its claws and begin the gruesome work of kicking its prey to death. Even without immediately killing its prey, the pack could then track the wounded animal, biding its time until blood loss and infection did all the heavy lifting, and Deinonychus could deliver the coup d'etat.

A quick note about the "terrible claw" itself: here's a pretty good BBC doc about Velociraptor mongoliensis in which they tested models of the back leg of these creatures. Interestingly, the claw wasn't built to disembowel: the underside of the scythe was round and dull, with no serrations. Only the point was sharp. The claw was therefore used as a stabbing weapon, puncturing arteries and trachea in the neck area.

Now for the hands.

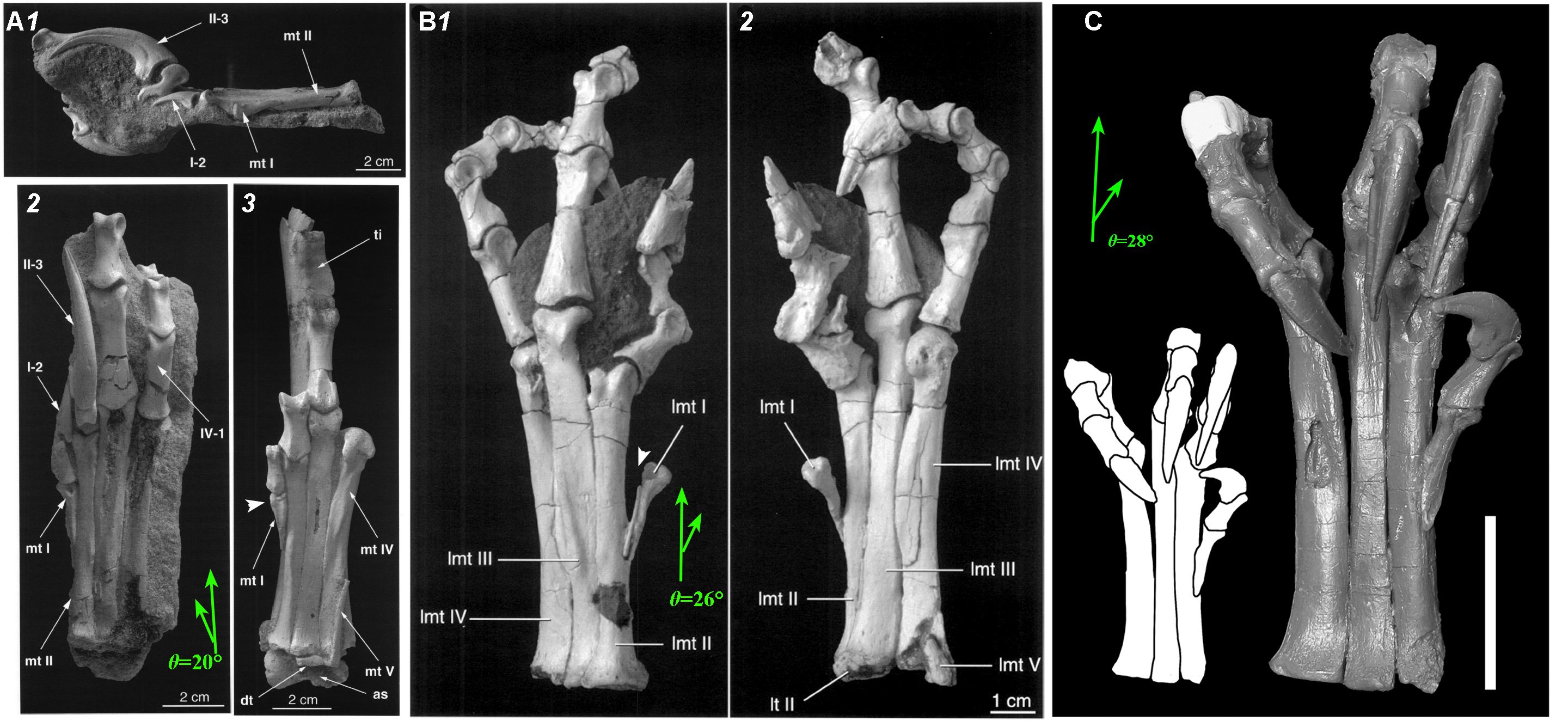

There's currently a craze for showing Deinonychus as a sort of heavily-feathered, land-roving hawk - much of this owing to the work of Fowler et al. (see above). Here's another image from their work:

| The Predatory Ecology of Deinonychus and the Origin of Flapping in Birds, Figure 1. |

Now, I'll admit to a certain bias; I'm definitely of the Jurassic Park generation, which would love to view Deinonychus as an intelligent, wolf-like packhunter, with dexterous killing hands. I also applaud the authors of this paper for having the courage to go against decades of accepted orthodoxy on the subject, and offering an alternative view of these amazing creatures.

At the same time, I have some deep problems with their reconstruction of Deinonychus arm function. The main thrust of the paper is that Deinonychus used "stability flapping" to maintain its balance atop a prey animal that was probably very much alive, then "mantled" the prey, as hawks do, both to prevent prey escape and to discourage other dinosaurs from poaching its catch. This predation behavior, according to their hypothesis, eventually leads to flapping in birds, and thus flight. The paper goes on to say that, since the wrist bones of Deinonychus were relatively stiff, this would proclude the kind of "snatching" behavior one would assume from such long, powerful hands.

This, to me, seems rather nonsensical. In dinobirds such as Archaeopteryx, which had nearly birdlike wings, the fingers are thin and trailing, with rather small claws. In Deinonychus, the fingers are very robust, with enormous claws. I fail to see why even a transitional animal would sport such massive, powerful front claws if they were only used for flapping and mantling.

This isn't just curmudgeonly fussing on my part, either. Let's look at some fossils. I present to you the famous "fighting dinosaurs" of Mongolia:

I believe this to be the original, and not a reconstruction - feel free to let me know if I'm wrong. On the left you see a Protoceratops; on the right, a Velociraptor. The 'raptor's right arm is caught in the Proto's beak, while the predator is slashing at the herbivore's neck with its sickle-claws (see above). Note the position of the left arm: it is clearly raking at the Proto's cheek bone, with the wrist flexed, and all the claws facing in the same direction - more like a hand than a wing.

Here's the same fossil, with more rock around it:

I include this version to show that the first image is as close to the original, intact fossils as possible, to rule out the possibility of scientific license. You can clearly see the raptor's left arm in the center of the fossil group, performing a very clear raking action. This is not to say that the Velociraptor did not perform a flapping action at some point; rather, that the hands of the creature were at least involved in some form of grasping, with the possibility of wrist torsion. In other words, the hands of Dromeosaurids (Deinonychus, Velociraptor, et al.) were involved in holding prey.

Here's a dinosaur-to-bird progression from David Peters over at Pterosaur Heresies:

This view, especially of Velociraptor, shows the joints especially well. (As to whether or not Dromaeosaurids could torque their wrists is a whole other issue; most recent reconstructions show them locked in place. I'd like to see the original fossils).

This leads me to a second issue, and one which continues to bother me about the recent crop of paleo-art: the assumed mass of Deinonychus' feathers.

"Feathered Dinosaurs and the Origin of Flight" traveling-exhibit model

The above model was originally just scaly, with the feathers added later. I'm actually okay with the majority of this reconstruction...except for the ludicrous, gauzy plumes attached to the hands. Did somebody go cheap at the feather emporium? Did they run out of primaries? Just looking at those arm-curtains gives me the itch for a big ole pair of scissors. Yuch.

Anyway...my problem with fully-winged arms, is that all those large feathers are a liability for an active predator. Assuming Deinonychus used its hands for grasping prey (which I do), long quills projecting past the fingers would get in the way, not to mention create drag in the attack. My problem is not with the idea of large feathers on the forearms, but of feathers that could interfere with gripping work.

I've developed a sort of "hybrid" interpretation: Deinonychus' arms utilized the downstroke of a flapping motion (see the large breastbone) alongside a forward snap of the hand. Here's a picture of the movement:

|

| ©2016 Richard M. Schlaack |

Whether or not the fingers had a full range of flexion (i.e., curl up into a fist) is irrelevant; all they needed to do was rotate the claws inward enough to grip into the prey.

As far as pelage goes: we do know that many of Deinonychus' relatives were covered in feathers; in fact, there is strong evidence that Velociraptor had quill-points on its forearm bones. It's no stretch of logic to conclude that Deinonychus itself was covered in feathers.

I favor this reconstruction, cropped from the "Feathered Dinosaurs" exhibit:

|

| (My modification of above) |

Basically the same body covering, complete with the crest and tail flourish...except the "hanging curtains" of the arms are tidied up into short, stiff primaries.

Here's my own reconstruction:

|

| ©2016 Richard M. Schlaack |

Note that the front of the snout is bare, and the neck generally is not hugely feathered. I based this on the look of most ground-hunting birds. From the African secretarybird to the fascinating (and very raptor-like) South American seriema, stalking birds tend to have less-feathered heads and necks, as well as raisable crests. I put a supraorbital ridge over the eye, as in modern raptor birds; this is based on the large knob in front of the orbit on the skull, which could have supported a cartilaginous "eye shade". Whether or not this was actually the case is up to far better paleontologists than I am.

All in all, it's a pretty conservative and not-very-revolutionary design; however, I find it much more plausible than some of the more fabulous fabrications circling around out there. Predatory birds as a whole - at least the serious ones - tend not to be wattled or have much in the way of outlandish ornamentation, favoring a sleek look and some combination of black-white-earth tone coloration. My red Deinonychus with a purple stripe may be a bit outlandish, but in my case I need to distinguish between a couple different species of predator with similar builds, and color is an easy way to do this.

Rick Out.

Comments

TORONTO — An Iranian

Would-be medical exec from Iran barred from Canada over alleged ties to Tehran's nuclear program. Ramin Fallah was labeled a security threat because he ...

You've visited this page many times. Last visit: 5/12/21

the hands on these animals were insane. im not yet convinced claws like that had great big wings over them getting in the way...